Henry Maudslay

Turning a key in a lock. Or building garden furniture. Or

helping a daughter assemble a model aircraft kit. Tasks with common underlying

principles: precision and interchangeability.

Toys made from plastic mouldings that are manufactured in large quantities. These components are designed with tolerances that ensure a suitable fit, themselves produced with steel tooling devised to give consistent dimensions. Various elements of the little aircraft kit can be boxed, confident in the knowledge that when unpacked the parts will fit together. Soon, a Spitfire or Typhoon is resting on the kitchen table, ready for painting and decals.

Similar principles apply in more complicated situations. Take an internal combustion engine, consisting of a cylinder head and block, a crankshaft, pistons, and connecting rods, all sourced from different, specialist suppliers. The components meet and are conjoined on an engine assembly line, with many other items, and must fit together, first time and every time. A major engine builder, assembling hundreds of units, cannot search for a particular crankshaft that mates with a given head and block. Precision and interchangeability apply.

These notions and the underlying cleverness are taken for granted today, but like much else in our civilisation, have origins in the recent past, often enabled by forgotten heroes.

Such a character was Henry Maudslay, whose career began modestly in a London munitions factory while still a child, late in the 18th century. Despite minimal education, this precocious young man soon learned carpentry and forging, perhaps gaining ideas he later deployed to great effect.

He came to the attention of Joseph Bramah, an inventor and entrepreneur who possessed an opportunity and a challenge. A padlock design, innovative for the era, and in demand. Unfortunately, though, little more than a design. The padlock consisted of many, closely-toleranced components, requiring skilled artisans, meaning few, expensive products. Undoubtedly shrewd, Bramah reckoned that Maudsley had the meticulousness to engineer a robust manufacturing process. A brilliant choice. Maudsley built machines of iron, not wood, to increase stiffness and repeatability. Together with innovative tooling, this enabled component production to meet the arduous dimensions of the lock. The machines were operated by regular employees, not artisans, so more could be produced at lower cost. An affordable lock was sold profitably.

Stiffness was an idea Maudslay deployed regularly. His screw-cutting lathe, used to cut cylindrical parts, was a leap. A rigid lathe, combined with a clamped toolholder positioned by a powered leadscrew on a planed surface, enabled the replicable cutting of screw threads. Such threads could be repeatably produced to a standard range of dimensions or pitches. He devised taps, allowing nuts to be made that would consistently fit a bolt cut with the same thread size. Interchangeable nuts and bolts. Fastening technology, used to assemble equipment ever since. Our present-day civilisation would not exist without this invention.

A more fundamental advance arose from this technology. Machine tools of various types evolved, incorporating the notion of stiffness. Components of all kinds could be precisely made, enabling interchangeability. Essential to the Industrial Revolution.

Maudsley did more, helping to build the first tunnel under the Thames and supplying the Royal Navy’s early steam engines, and became prosperous.

Perhaps, though, he should be remembered for the nut and bolt.

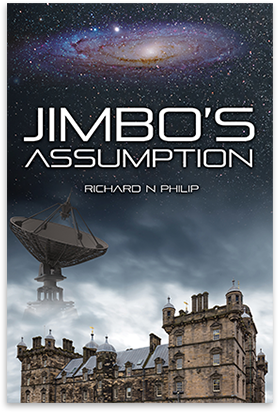

Henry Maudslay is a pioneer set to feature in a sequel to Jimbo’s Assumption - RNP

Post Views : 27